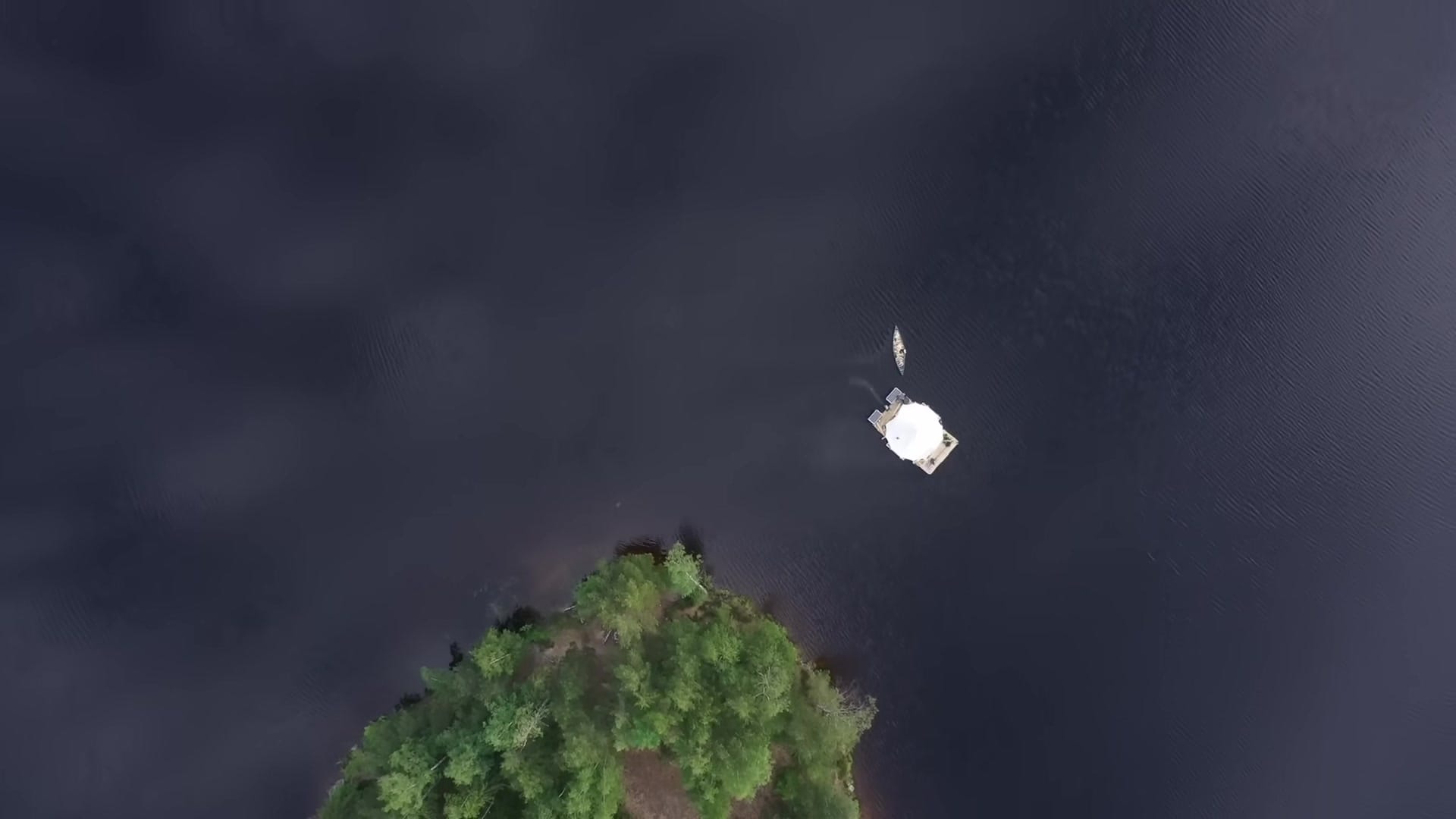

A 3.9m Raft That Fits a 5m Tent — Floating Off‑Grid in Sweden

They live in a tent on a self‑built raft and move slowly across a lake system.

The setup is minimal, deliberate and designed to fit local locks.

Meet the Raft — size, build and why it fits the locks

The raft was built quickly over a few days and finished with fittings added later.

The frame is impregnated wood for weather resistance and longevity.

Buoyancy comes from twenty‑eight 200‑liter barrels lashed under the deck.

Overall footprint is 3.90 m by 7 m so it will clear the canal locks.

The build balances cheap, available materials and portability.

Barrels + timber give a stable platform for a tent and a small deck, not a heavy yacht .

The modest length and sub‑4m width are intentional so the raft can pass through 4m locks .

Construction and finish prioritize simplicity over luxury; the raft’s rough edges are part of the design .

The Tent Home — layout, cozy bits and storage

A Sibley 500 Protech bell tent sits on the deck as the living space.

The model has two doors—front and back—useful because the engine and steering are at the stern .

A plexiglass door insert brings daylight and view while sealed against cold or mosquitoes.

A tarp can be rigged for extra shelter on rainy days, though it must be taken down before moving.

Inside is mostly storage at the entrance and a convertible bed/couch that doubles as seating.

Under‑bed boxes keep clothes and instruments tucked away, which saves floor space .

A small woodstove with glass on three sides provides heat and a visible flame for comfort.

A self‑built table and borrowed chairs make a compact kitchen and dining nook for cooking and playing cards.

Power, Engine and Fuel — solar, batteries and the 6 hp motor

Propulsion is an older six‑horsepower two‑stroke outboard—simple and secondhand.

The raft weighs roughly 1.5 tonnes, so the engine feels underpowered when pushed.

Two 150‑watt solar panels sit aft to keep the batteries topped up during daylight.

Those panels feed three batteries housed under the deck for lights, devices and minimal appliances.

Petrol storage and oil live under the solar array with about 80 liters capacity for extended runs.

Choice of a cheap petrol motor trades noise and fumes for affordability and repairability .

An electric outboard is the stated upgrade priority for quieter, cleaner travel in future seasons.

For now the petrol system and modest solar bank handle basic electrical needs without a fridge .

Cooking, Water and Waste — daily routines onboard

Cooking is usually on a small fuel stove; when it’s cold the woodstove doubles as a cooking surface.

Hot water is produced by heating a pot on the stove for washing and occasional showers.

When passing locks or villages the raft can refill drinking water from taps and reinventory supplies .

Lake water is used too, treated with purification tabs when used for drinking to be safe .

Food is simple and shelf‑stable: pasta, rice, grains, legumes and spices in a dedicated box .

There’s no fridge, so leftovers are eaten quickly and fresh produce is restocked at towns .

A dry composting toilet is kept as a backup; the team usually uses shore facilities or a simple dug hole in remote spots .

Biodegradable‑soap lessons have led to washing at least 60 meters from the waterline to protect the lakes.

Moving Around — steering, locks, anchors and the handcart

The route is a lake system connected by the Dalsland Canal and a series of locks that enable long-range travel.

Transit is deliberately slow—around four kilometers per hour—so stops and anchoring matter as much as travel time.

A front steering mechanism uses two metal wires that pull the outboard rudder from the bow for directional control.

When parked the raft is secured like a spider between shore lines: two ropes tied to trees plus an aft anchor to prevent drift.

Small settlements become resupply points to grab groceries and top up petrol before the next remote leg.

A canoe serves as a practical shuttle for hauling construction wood and gear to shore .

Locks require careful setup—flipping or lowering parts of the tent can be necessary to clear narrow chambers .

Slow, intentional navigation means more time for maintenance, chores and picking quiet bays to sleep .

Costs, Challenges and What They’ll Change Next

The lifestyle is low‑cost overall but fuel is the single largest ongoing expense after food.

Space is the biggest non‑monetary constraint—two people in a compact tent on a small deck compresses belongings and routines.

Weather is constant background work: wind changes overnight can create waves that jostle the raft and demand repositioning.

Noise and fumes from the petrol outboard are a persistent tradeoff; an electric outboard is the stated top upgrade for quieter, cleaner cruising.

Other practical needs include better privacy for the toilet when in populated areas and more stable tarping solutions for rain .

Despite the compromises, the setup is intentionally minimal so everything owned fits into the living space and can move on short notice .

If the next season brings an electric drive and a few refinements to anchoring and steering, the raft will get quieter and more self‑sufficient .

The current configuration is a working pilot — compact, cheap to run in many ways, and built to be improved.