He Built a House That Lives in a Pond

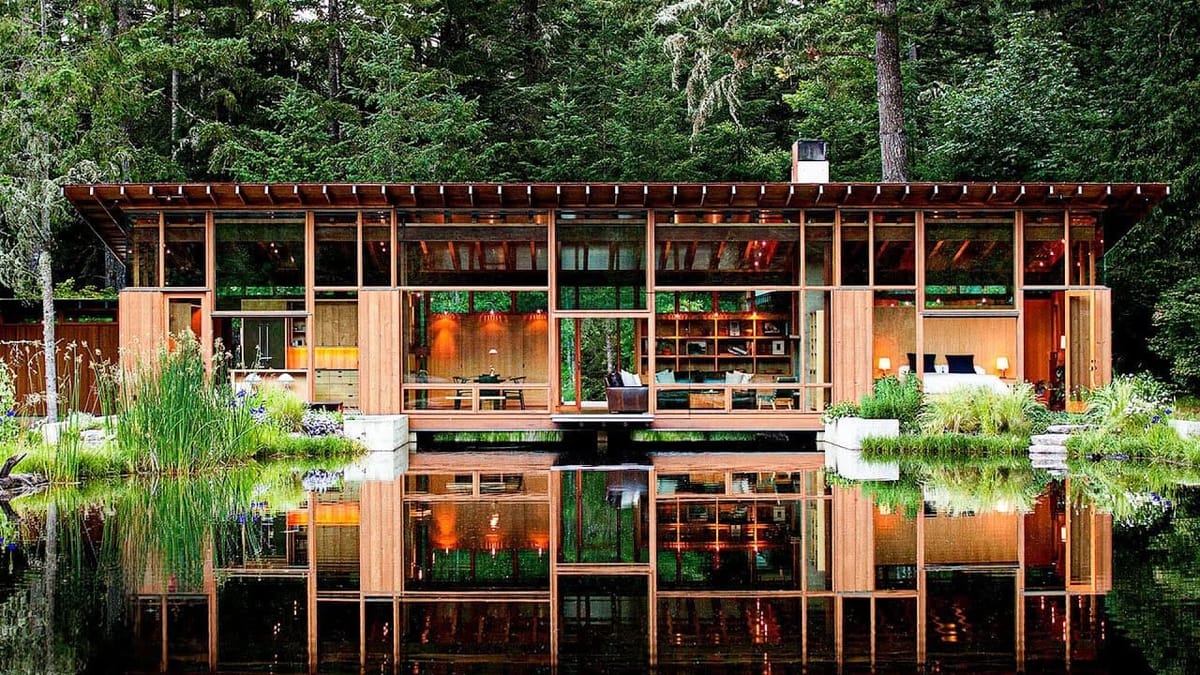

Architect Jim Cutler designed a home that doesn’t face nature—it dissolves into it. His trick: choreography, steel, and an 800-pound door that makes water part of the room.

The color-door test

Jim has a favorite scene: the moment Dorothy opens a door and the world flips from black-and-white to Technicolor. That’s how he wants architecture to land—like a reveal you feel in your ribs.

He calls it choreography: you move; the building responds; your senses do the rest. When architecture amplifies a place, the place becomes the main character.

He’s the principal at Cutler Anderson, and a decade ago he drew up this home with one audacious premise: make the building and the pond inseparable.

From hilltop fantasy to habitat reality

The clients had picked a dramatic hilltop. Gorgeous, sure. Also a forever-parking-lot problem. Cars are easy to bring in and maddeningly hard to banish.

Walking the land, Jim saw a clearing—a half-silted logging pond and a stubborn old stump—and declared, “Here.” Not above the landscape, but inside it.

His why was simple and radical: build where life already happens, then protect it. If they made water the heart, life would come knocking.

He wasn’t wrong. The owners now read the day like a wildlife calendar—flickers working the bugs, then swallows, then bats stitching the dusk. The pond made time legible.

Architecture, Jim says, should bring you to an emotional understanding of a place. Feel it, and you’ll want to keep it alive. That’s the whole point.

When your house tunes you to the living world, you begin to hear what’s been speaking all along.

The approach that squeezes you

Guests park far away on purpose. The path tightens as you walk, the sky narrows, and your senses start to lean forward. It’s architectural deep focus.

At the door, the compression peaks. A hint of water leaks into view, just enough to spark curiosity without giving away the punchline.

Contrast is the trick: tight makes open feel monumental; shadow makes light feel electric. The door is the foil; the pond is the reveal.

Even outside, Jim slips you glimpses over the low roofline so your body knows there’s a clearing ahead. Your feet keep moving; your eyes are already there.

Steel that disappears, fire that steadies, roof that shelters

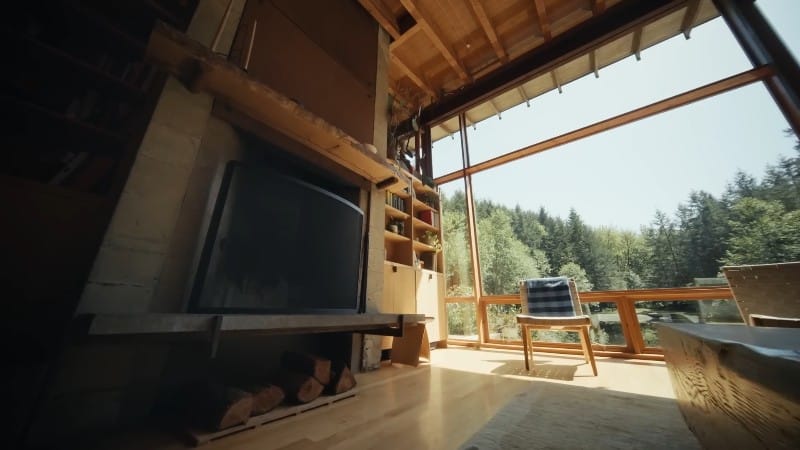

Inside, the beams are steel—thin enough to keep the view intact, strong enough to carry the span without hogging the horizon. Material honesty as magic trick.

Jim listens for what each material wants to do: steel carries, wood warms, water hosts, forest instructs. His job is to turn all that into harmony instead of noise.

The fireplace isn’t just cozy; it anchors the whole structure against sideways forces. When the earth shrugs, the hearth holds fast. Form, meet tectonics.

The roof runs as one continuous plane, turning the house into a pavilion—shelter without severance, like a held breath between indoors and out.

Doors that put your toes in the pond

Here’s the flex: a counterweighted door you can lift with one hand, even though it weighs about as much as a small car engine. The counterweight? Slabs of lead riding quietly in the wall.

There are three of these doors—kitchen, living room, bedroom—so you never have to choose between being in the house or in the pond. You can be both.

They even carved out a proper diving edge so cannonballs don’t splash the oak floors. The line between architecture and swimming dock is deliciously blurry.

At the kitchen, a window sits exactly where the range works best, because design is only elegant if it cooks well on a Tuesday. Practicality with a view.

The outside is part of the floor plan

To reach the guest house, you walk outside. That’s intentional. A few steps of weather recalibrate your senses: wind in the trees, moon over water, rain stippling the pond.

Jim learned this at home: even a 35-foot dash to a little cabin is enough to make an ordinary night feel like a ritual. Why not build that feeling in?

Most of the materials are local to the Pacific Northwest—Douglas fir, cedar, inventions born here like glulam and vertical-grain plywood—each used within its nature.

Concrete pads line up along the water’s edge like remnants of an ancient pool—submerged here, revealed there—nudging your brain to sense time layered into the site.

Clothing the family, teaching love

He treats architecture like tailored clothing: public zones where life happens, private zones where it can retreat, and clean decision points so you can choose one or the other without friction.

Custom beats “one size fits all,” especially when the client is a family with actual habits and quirks. Good tailoring is invisible until it isn’t; then you can’t live without it.

Bring people to beauty, Jim says, and they’ll fall for the living world. Once you love something, you defend it—which might be the most architectural idea of all.

So yes, there’s steel and detail and bravura. But the quiet thesis is simpler: if your home teaches you to notice water and bats and wind, it’s not just shelter—it’s a lifelong invitation to care.