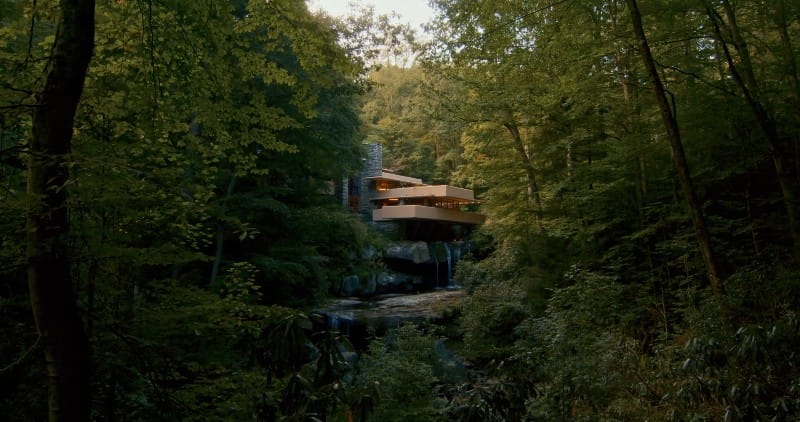

Inside Frank Lloyd Wright's Fallingwater

Tucked into the woods of southwestern Pennsylvania, this place feels alive. The house and the stream share the same heartbeat, and you feel it the second you step onto the terrace.

A house that changes with the weather

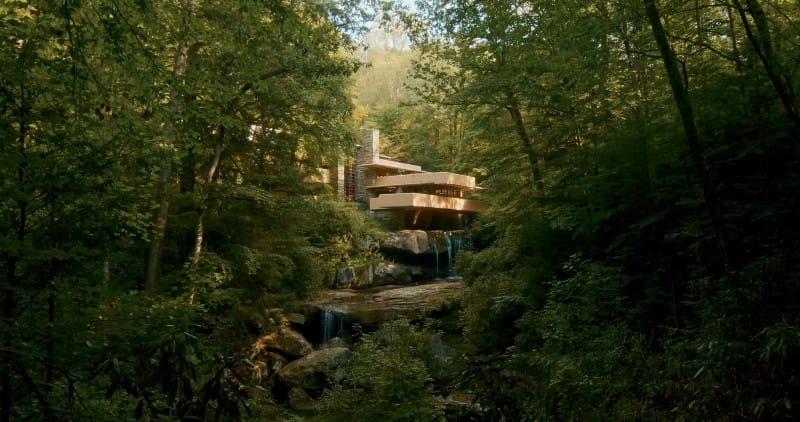

In winter, the stone turns cool and silvery; in fall, the terraces glow like the leaves. Every season shifts the mood.

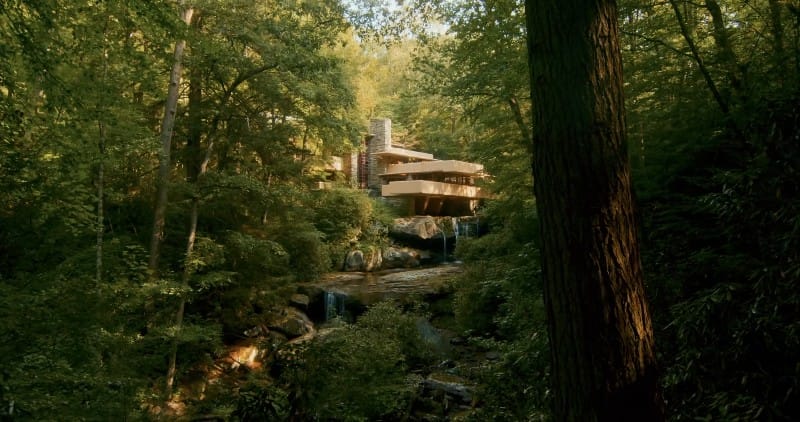

Morning light slides across the cantilevers and makes the edges look razor sharp. By late afternoon, everything softens.

When it rains, the sound of the falls swells and the air goes misty—suddenly you’re standing inside the weather.

Even the interiors feel different in a drizzle; the windows haze slightly and the forest smell drifts in.

It’s not just pretty—there’s a deep, grounded calm here that ties straight back to the landscape.

Finding Fallingwater

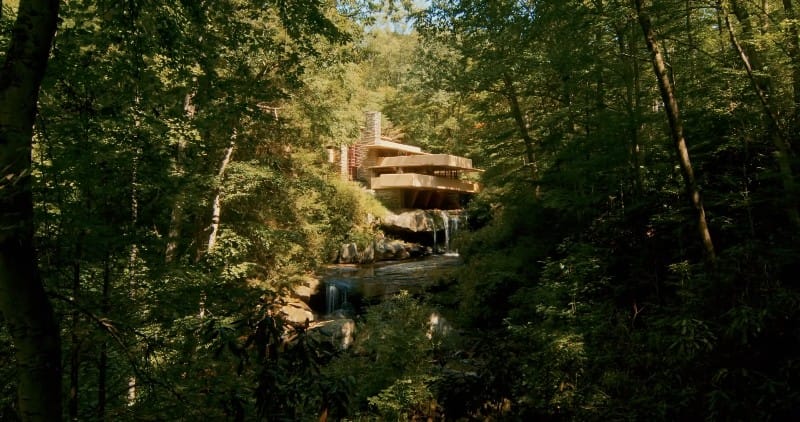

It sits in Mill Run, Pennsylvania. You wind through tall hemlocks and then—there it is, hovering over the stream.

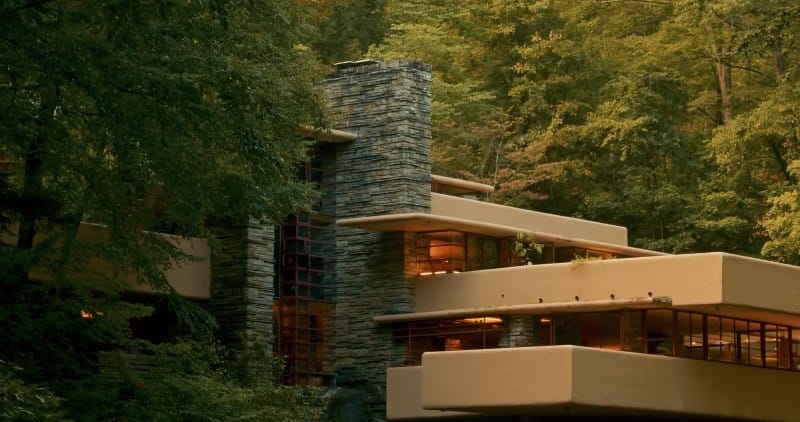

Frank Lloyd Wright designed it to feel inevitable, like it grew here. Even the palette matches the rock ledges.

He didn’t design a house to look at a waterfall. He designed a house that lives with one.

Stone walls feel like cliffs; concrete slabs shoot out like the rock shelves along the creek.

The Kaufmann family made this their escape from Pittsburgh, and you can see why—clean air, cold water, endless trees.

There used to be a rustic summer camp out here. The woods still carry that spirit of retreat.

Back when Pittsburgh smog was thick, this place was the antidote—clear, bright, and quiet except for the water.

The family eventually bought the land to make a proper weekend place. That single decision changed architectural history.

The son was the one who pushed toward art and design, and that nudged everything in this direction.

He dove into ideas about organic architecture—the kind that fuses building and landscape. You feel that here every second.

He went to learn where Wright taught, and those threads eventually pulled the architect to this creek.

Soon the whole family was in on the vision: a real house, not a camp—something timeless and rooted.

Wright got the job. Standing here now, it’s hard to imagine anyone else drawing these lines.

The wild decision that made it iconic

Everyone expects the house to sit on the bank, looking toward the falls. The bold move was to perch it directly over the water.

You don’t stare at the falls from afar. You feel them rumbling underneath. The surprise never wears off.

From below, the cantilevers stack like limestone shelves. From above, it feels like walking on air.

Inside, the hearth is anchored by a boulder left exactly where it was. It’s the same rock people once basked on in the sun.

The fire is literal and symbolic center here—the room spins around that stone.

It all works like a seesaw: heavy stone at the back balancing those long concrete arms floating over the stream.

Built from the hill it sits on

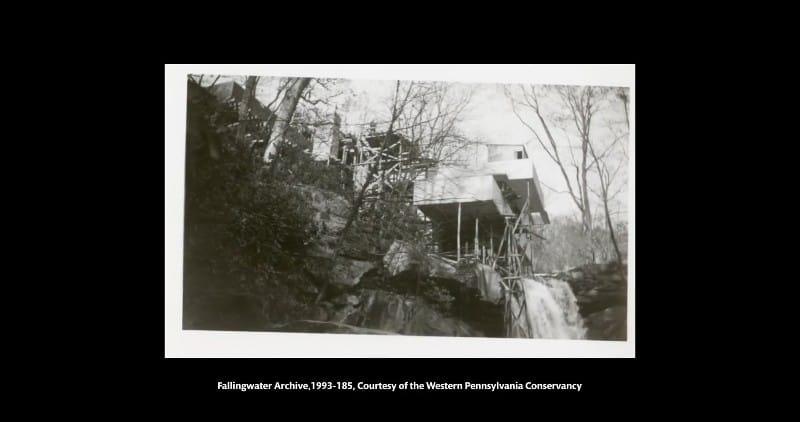

Design began in 1935. The drawings read like choreography—a dance between rock, water, and light.

By December 1936, workers were on-site pouring forms and stacking stone.

By the end of 1937, the family was using the main house, with more to come.

The guest house arrived a bit later up the hill, tying the ensemble together by 1939.

All told, about three years transformed this bend in the creek into an icon.

The stone came right from the site; the sand and aggregate did too. Even the materials are local memory.

It’s modern, yes, but also deeply handmade—chisels, mallets, and a lot of careful hands shaped this place.

Rooms that push you outside

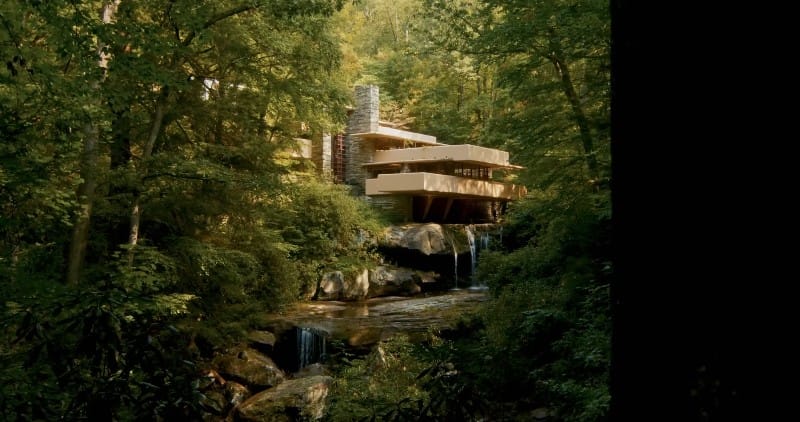

The main house totals about 10,000 square feet, and roughly half of that is terraces. It’s all about being outdoors.

Doors pivot and disappear so easily you’re halfway outside before you notice.

Inside feels like an antechamber to the terraces—cozy, low, and then suddenly you’re in the open air.

The whole plan springs from the waterfall’s line; set a triangle, swing the axes, and the house snaps into place.

That orientation lands perfect southern sun across the broad slabs in the late day.

From the streambed, the house seems to hover—weightless and impossible. Up close, it’s snug and warm.

The two—house and waterfall—feel inseparable now. One completes the other.

The four elements meet in one room

Stand in the main living room and you can trace the axes like a cross laid over the landscape.

Earth is at the entry: rough stone, low ceiling, solid underfoot.

Air pulls you straight out to the terrace; you can’t help but step through.

Fire anchors the hearth—warm, central, magnetic.

Water waits down the steps—yes, actual stairs slide right toward the stream.

More forest than house

The family started buying up land here to protect the woods, and that effort kept growing.

Today, thousands of acres surround the house—nearly 5,200—so the forest can breathe and recover.

It’s all about safeguarding the watershed that threads through the middle of this landscape.

Healthy woods make stronger streams, especially when storms hit hard and fast.

The creek slips under the slabs and crashes into a broad pool, cool spray drifting upward.

From private retreat to public treasure

By the 1950s, the original owners were gone, and the house passed to their son.

He kept using it as a getaway for a while—imagine holidays here with the windows thrown open.

Life eventually rooted him in New York, wrapped up in design and teaching.

In the early 1960s, he made the move that opened the gates—he gave the house and land to a conservation group.

The goal wasn’t to freeze it in time. The idea was to conserve it, so it could keep evolving with the woods.

You can see that approach in the way the place is cared for—thoughtful, adaptive, alive.

Best part: it isn’t private anymore. Anyone can come and let this place rewire how they think about nature and design.

Tours began back in 1964—people have been streaming down this path for decades.

This year marks a big milestone on that timeline—sixty years open to the public.

It also stands as one of the earliest modern houses to open as a public site.

A classroom in the woods

Education drives everything here. Even on a simple tour, you feel like you’re learning by osmosis.

There are deeper dives too—residencies where students and pros camp out in the ideas as much as the forest.

High Meadow sits nearby, a low-slung retreat for workshops and late-night design discussions.

It sleeps around sixteen, perfect for teams sketching at dawn and debating details after dinner.

The groups span from high school to working architects—everyone wrestles with the same big questions.

Getting special access means you can study how these cantilevers actually meet the stone—there’s no substitute for seeing it.

People build models, test ideas, and translate Wright’s lessons into contemporary problems.

There’s something here for any age and any kind of learner, which makes the place feel welcoming and useful.

Why it sticks with you

The roar of the falls becomes a soundtrack—you notice it, forget it, and then notice it again in waves.

Railings bead with moisture and the air carries a cool kiss off the water.

The forest has that rich, leafy smell—fresh earth, wet bark, a hint of hemlock.

All those sensations layer together until the place imprints itself. It stays with you long after you drive away.

By sunset, the terraces feel suspended in amber light, and the house hums quietly above the stream. It’s pure awe.