The Guy Who Built a Floating, Off-Grid Home Because He Wanted Morning Ducks

Jay wanted water in his life—like, right there under his feet. So he built a 700-square-foot float home that runs itself, sips energy, and quietly shrugs off winter storms.

He Wanted Water. He Built a House That Floats.

Mornings are kind of absurd on this dock. Coffee in hand, ducks cruising by like neighbors, paddlers waving, his sailboat tied up a few steps away. It’s calm, and you get why he aimed his entire life at this.

The thing is, he didn’t just move into a place here—he designed and built the whole float home. Off the grid except for being tied to the dock. No power line, no sewer hookup, no city water. Just a tidy little system that he keeps tweaking.

Okay, But What Is This Thing Sitting On?

Under the house is a barge he built himself: 16 feet wide, 40 feet long, 3 feet deep. Four separate watertight boxes for safety—very belt-and-suspenders. Locally harvested cedar for the bones.

He skinned it with plywood and then went heavy on fiberglass—four layers of the tough stuff, plus epoxy. It turned the hull into this rock-solid platform he could deck and seal before framing the house.

On top: a 14-by-34 main floor and a 12-by-24 second floor. About 700 square feet of heated living space, with bonus storage tucked down in the hull. It’s compact, but not cramped.

Inside: simple, warm, no fluff

Walk in and it’s all one cozy space—sofa, kitchen, and a bathroom with shower and a composting toilet that’s still getting finished. Upstairs are two real bedrooms, not token closets, each roughly 13 by 14. It’s a normal home that just happens to float.

There’s no upstairs door to the deck—wind loves to find leaks—so you pop up from the main deck and get 360-degree access up top. The temporary ladder is on borrowed time; he’s building compact stairs out of fir. Kind of nautical, kind of cabin.

Power-wise, he tucked a sealed battery bank under the sofa: 740 amp-hours fed by solar on the roof. The wiring isn’t house style, it’s yacht-grade—tinned, stranded, corrosion-resistant. Overbuilt in the best way.

Heat that sips pellets and minds its mess

The primary heat is a pellet stove with a hopper that swallows a full bag and just chugs along for a week. He stores a literal ton of pellets down in the hull and only used 14 bags last winter. That’s… not much.

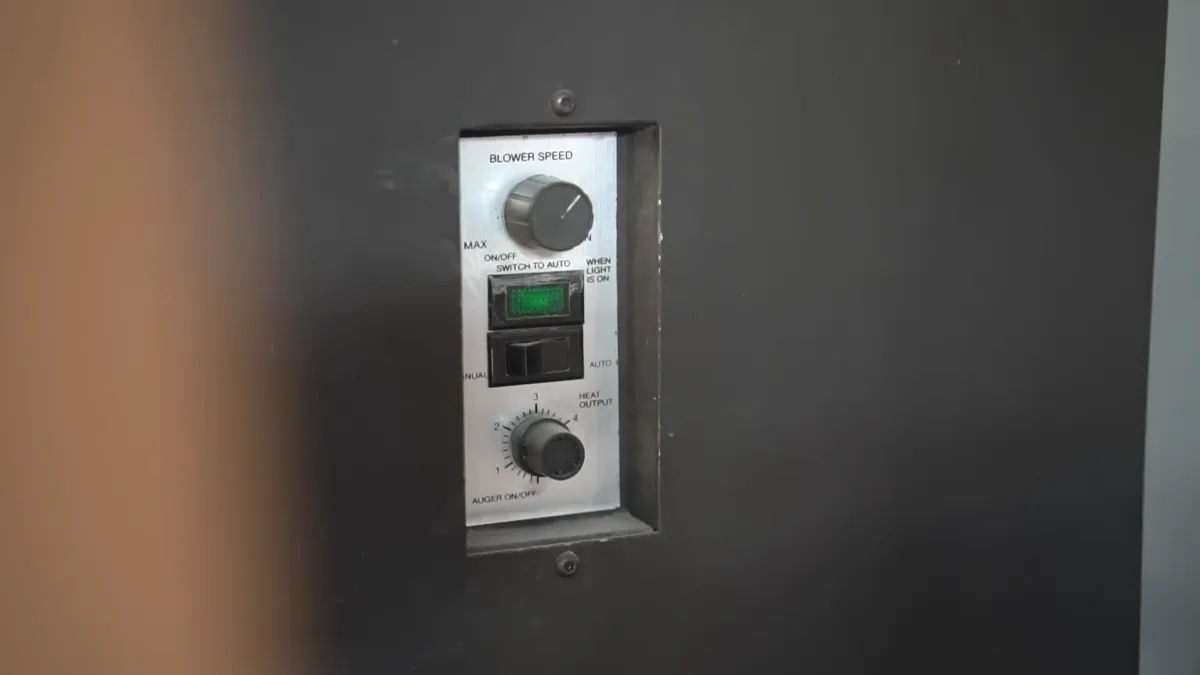

The waste is almost nothing—about a quarter cup of ash after a week. The controls are old-school simple. On low when the lake is quiet, up to high when winter gets moody.

There’s a backup propane furnace on deck, fed by two 60-pound tanks. Same fuel runs the small RV range and a couple gas lights for quick warmth in cold starts. Belt, suspenders, and a scarf.

Safety is layered: carbon monoxide detectors in rooms, gas detectors down in the hull, and a 7-pound Halon canister that auto-dumps if the temperature spikes. It covers the whole heating zone. He thought through the scary stuff.

The catch: whatever comes aboard, you haul

He can walk to town for groceries and parts, which is great when the sun’s out and less cute when November throws sideways rain. Still, it’s part of the deal. Dock life is weather, not calendar.

Everything that arrives has to be carried in—propane, pellets, food—and everything that leaves has to be carried out. No curbside magic. It changes how you think about consumption, fast.

Built like a boat, tight like a thermos

The place is spray-foam insulated wall-to-ceiling. It wasn’t cheap, but it acts like a vapor barrier and glues the structure together. When the lake bumps the hull, the whole home moves as one, no creaking or weird twists.

Water comes from the lake—pumped from about 25 feet down where the current stays fresh. First a strainer, then a sediment filter, and a five-stage reverse osmosis setup for cooking and drinking. Clean, simple, no drama.

And nothing goes overboard. Gray water runs into a grease trap under the kitchen, then into a container filled with screened maple woodchips where microbes get to work. From there it passes through activated charcoal.

After treatment, a sump sends it up to hidden piping in the soffit that drips into planter boxes and hanging baskets. Soil and mulch do the final polish, and the sun takes it from there by evaporation. It’s a tidy loop.

At peak summer, the system can handle about 40 gallons a day. Winter’s trickier, so he hijacks waste heat from the pellet stove—there’s a loop through the burn box that warms a sump and turns gray water into vapor. Honestly, pretty clever.

Black water? Just the composting toilet, running quietly and doing its job for a year now. Not glamorous, but effective.

Why he did it, and why it stuck

Before this, Jay owned a house out in the trees, a 20-minute drive from town. It was beautiful and also bossy: mowing, plowing, fixing, repeat. With kids getting older and always headed to activities, the commute and the upkeep were swallowing time.

He wanted to cut housing costs without squeezing his family into a hard-to-manage life. Living on a boat didn’t fit with teenagers. Then he saw float homes in Vancouver and the idea snapped into focus—spacious enough, still on the water, and buildable.

So he went for it: local materials where he could, hands-on work to keep costs down, and a genuinely smaller footprint. The goal wasn’t to suffer—it was to show his kids a different version of a good life. Turns out, ducks and paddlers help.